For Play

For Play, Shaping Sexuality. Sex and design share a long history: the oldest dildo ever to be found dates back 28,000 years. More important than the attributes however, is the way we shape our experience. Human sexuality is defined in discourses and images that change over the centuries. In today’s erotic landscape, dominated by porn and commerce, curators Sanne Muiser and Tom Loois often miss the kind of spontaneity and inventiveness that can make sex such good fun. So they asked over 30 artists and designers for alternative visions: more playful, vulnerable, more original.

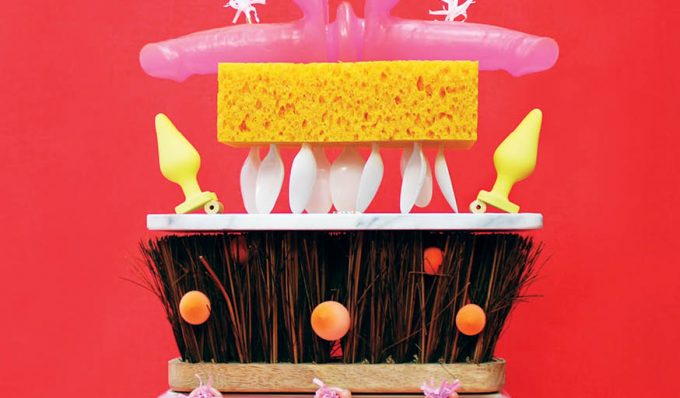

Image is made by Studio Pluis

For Play is centred around two themes: physicality and imagination. One of the aspects of the body being explored in the works is its impermanence, like Marrie Bot’s tender Geliefden (Lovers) or the more confronting Transience that the curators commissioned Pleun van Dijk to make. When the infirmities of old age become a burden, we can now turn to Love Assist, a series of aids developed by Glenn da Silva, who believes that people tend to have less sex later in life only because their bodies become less accommodating.

Physical decline might be a source of shame – but why is it that most people wouldn’t be comfortable to discuss their sexual experiences in the first place? Why is it that we seldom give in to our lusts in public? According to sociologist Norbert Elias it is the result of a gradual process of civilisation. In The Civilisation Process he describes how, since mediaeval times, people have been behaving increasingly rational and have been showing more and more restraint in numerous areas. Eat with a knife and fork, don’t pick your nose or urinate in public, wash yourself daily. Sex has become an increasingly private matter, meant to be conducted in the bedroom, while carnal desires became something to be ashamed of.

In the 19th century, this development led to the notion that children were best kept ignorant of anything related to sex. And despite the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s many parents and educators tend to hold on to the belief in children’s innocence. As a result, Barbie dolls still have no nipples, nor a vagina, and Ken remains a eunuch. In response to this censorship Janne Schimmel made the work Parts to Play With. The modelling-clay figures with their abundance of body parts other dolls have to do without are reminiscent of the ‘desiring-machines’ described in Anti-Oedipus by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. In the book they argue against the repression of desire. They would rather see the world as a ‘body without organs’ where all kinds of desiring-machines connect to each other in ever-changing configurations to continue the flow of desire, free from repression.

Repression of desire is at play in Dign Kosse’s Minimal Dress and becomes very prominent in Caged, a work by Bart van Hess confronting us with our blind impulses that are only just kept in check. In Hiding from Humanity philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that shame originates from a sense of incompleteness, of a lack of control. Shame of our imperfections is being reinforced by a tendency in society to stigmatise people and groups who are not ‘normal’. The consequences for the relationship with our body and with sexuality can be devastating, as shown in Becoming by Dorota Radzimirska. Shame seems to have inflicted a almost fatal wound to self-esteem and confidence and it takes a lot of loving support and revalidation to restore it.

Arnoud Hollemans moves beyond shame. The dicks he draws look beautiful but it is the title, Family and Friends, that makes the work truly significant. Indeed, penises come in numerous shapes and sizes. But usually, this kind of intimate knowledge of someone’s private parts is reserved for lovers – not for relatives or peers. And then, many people are less acquainted with their own body, as Michelle Degens rightfully points out. Her Vulva Versa gives a definitive answer to the question whether your vagina looks normal: variation is the only norm acknowledged by nature.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Physicians like Magnus Hirschfeld and Richard von Krafft-Ebing no longer considered ‘deviant’ sexual acts – that were not aimed at procreation – as vices or crimes but rather as symptoms of a ‘perverted’ sexuality that could be treated. Heterosexuality (defined as an excessive desire for intercourse with someone of the opposite sex) was just as deviant as homosexuality, bisexuality, exhibitionism, voyeurism, fetishism, sadism or masochism. Gradually, the idea took hold that sexual preferences are not pathological symptoms but part of someone’s identity: you are who, or what, you desire

Today, the idea of a fixed sexual identity is giving way to the understanding that desire and lust need not always remain the same. They can change depending on the people we meet, the circumstances of our lives, the changes in the body. In the end, we actually quite resemble those desiring-machines in a ‘body without organs’. To embrace diversity is the second theme of For Play, Shaping Sexuality: the imagination that explores the area between desire and the deed, that expands it, bridges it and fills it with new varieties.

The exhibition opens with Mechanische Balts (Mechanical Courtship) an installation by Joost Gehem and Tiddo Bakker inspired by the breeding ground: a place where animals meet for their mating ritual. The breeding ground and the ritual character of the mating dance offer an interesting alternative for swiping on Tinder of Grindr. The finger swiping left or right is replaced by a licking tongue in Dani Ploeger’s Fetish. The work not only comments on our fascination with the online world but also on the seductive design of our gadgets.

For Play is geared towards Homo Ludens or the Playing Man. Jolene Carlier’s Sex-Machine was inspired by a Fisher-Price Activity Center and Jan Pieter Kaptein uses the bedchamber as the setting for Bedtime Games, an installation with a life-size objects that invite visitors to let their imagination run wild. In and around the house, Margriet Caens and Lucas Maassen deploy furniture as symbols for human relationships. Let’s Stick Together exists of couples of cabinets and cupboards bound together – two individuals, each with their own drawers and doors, that have found a new balance of connectedness and mutual dependency.

Desire and power are being addressed in several performances programmed during the Dutch Design Week. In For I am Dinosaur Gazelle Imke Zeilstra explores her position as a woman in relationship to men, the audience and the art world, while Merel Stolker relates to an art object in the form of a man-sized dildo in Him.

Since the Stone Age, very little has been added to the dildo, by the way. Bluetooth and vibrations, that’s about it. But Maud van der Linden’s Masturbatie Pak (Masturbation Suit) and the Metamorfosis by Bastiaan Buijs might actually be valuable contributions when you are playing with yourself, just like Janne Schimmel’s Wat je zegt ben je zelf (Your words define you), that is very sensual without necessarily being stimulating or aimed at reaching an orgasm. The same can be said of Harm Rensink’s Foot Spa, a space inspired by Japanese traditions and rituals where you can give your feet a salt bath and clear your mind when it is reeling with all the impressions in MU.

Jason Page supplements the exhibition with the Backdoor Audio Tour that is composed of skype conversations he had with the makers of the various works. The tour blurs the boundaries between public and private and invites the visitors to participate. And for those who can never get enough of it, there is homework from the National Sex Rabbi: do try this at home!

relevant articles DEZEEN , Vrij Nederland (dutch, pay wall)

director; Angelique Spaninks, co-curated Sanne Muiser & Tom Loois,

text; Nanne op ’t Einde

location; MU, Eindhoven

image; Studio Pluis